The Simplest Database You Need

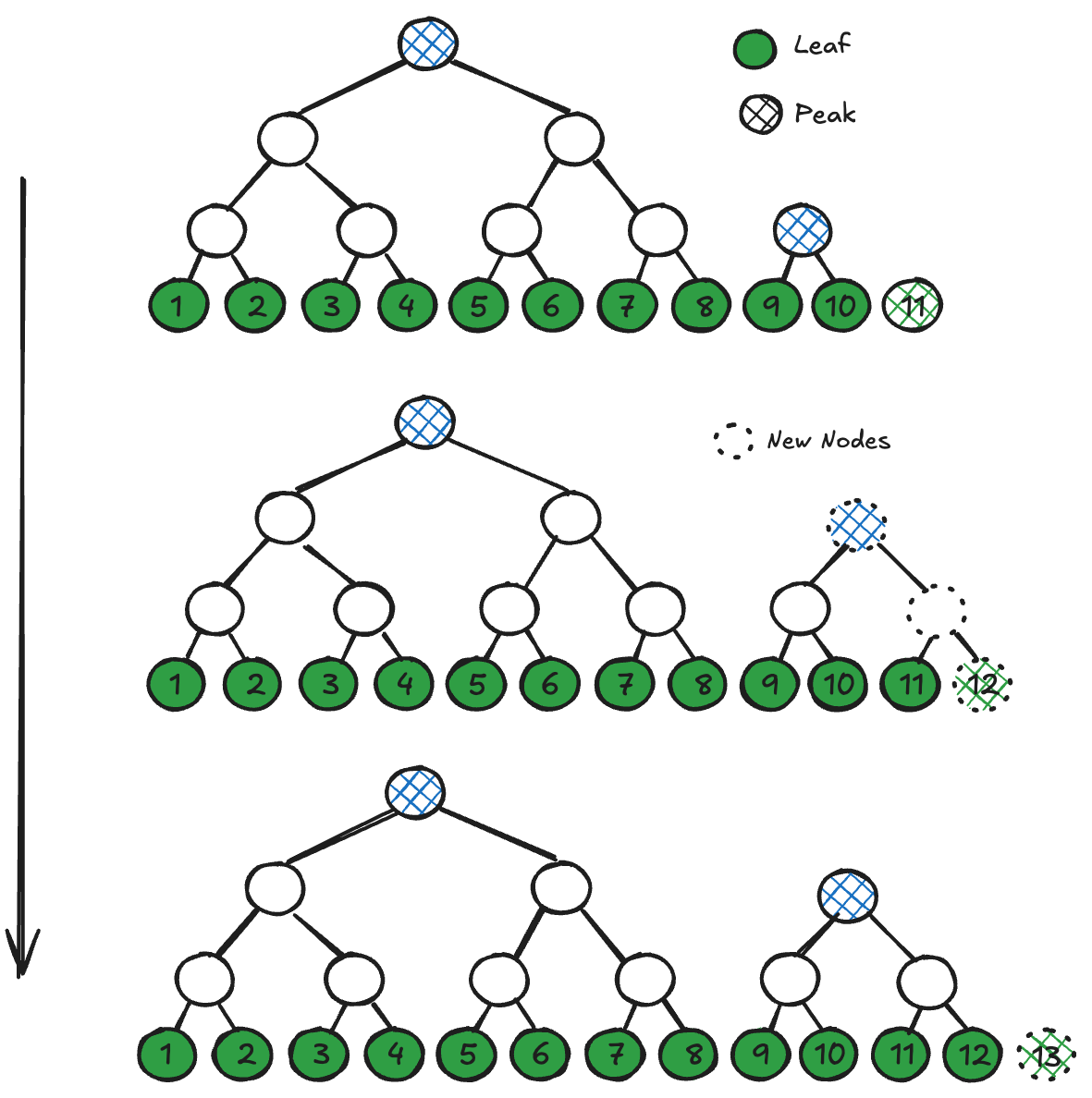

In a previous article, we detailed the unique properties of the Merkle Mountain Range (MMR) that make it an excellent fit for authenticating data in high-performance blockchains. Recall that MMRs are an authenticated data structure (ADS) from which an untrusted server can efficiently prove inclusion of any element within a growing ordered list, as depicted below:

Here, we'll dive into how the construction can be extended to create a lightweight authenticated database (ADB) capable of storing and proving mutable blockchain state with minimal amplification. We call the first of these MMR-powered ADBs adb::any, and are excited to share that it is now available under an MIT/Apache-2 license.

The primary limitation of the MMR compared to a more typical Merkle tree structure is its lack of support for removing elements from the list over which inclusion proofs can be provided. This restriction, at first glance, might appear to prohibit an MMR from being used to build a mutable database where keys take on values that change over time. However, append-only MMRs are a natural fit for authenticating log data. Instead of viewing our database as only a snapshot in time, the basic idea we'll build on is to maintain an MMR over the historical log of all database operations performed up until the present state.

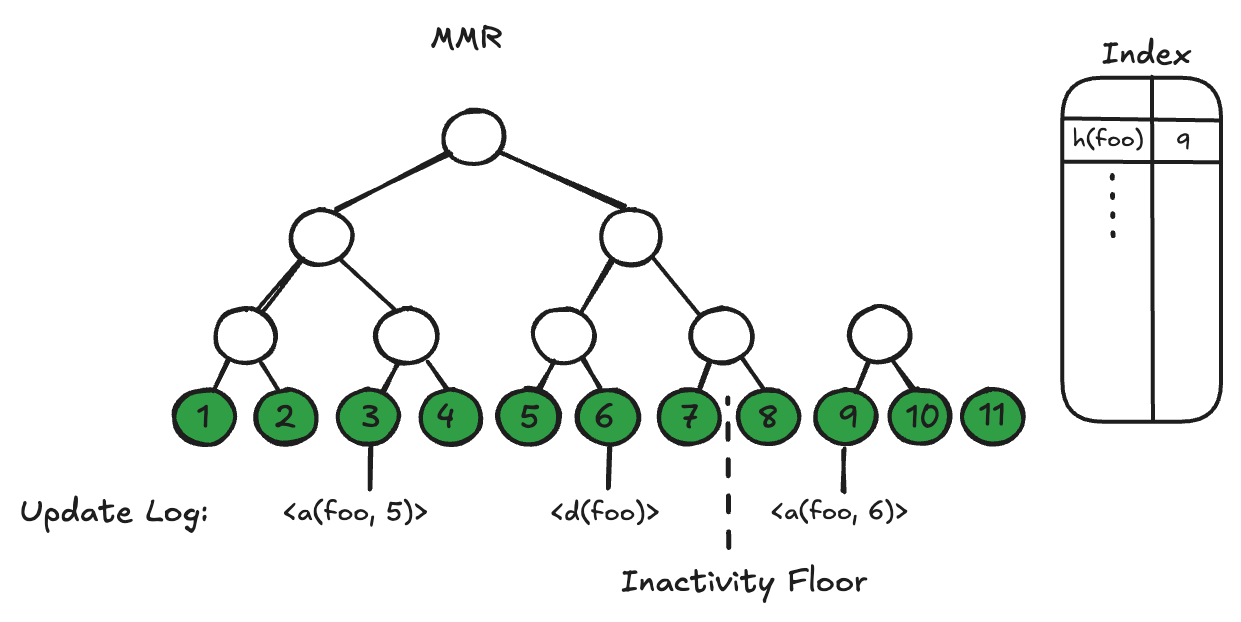

Let us consider two basic operations, assigning a key a value and deleting a key's value. Each operation applied to the database gets added to a persistent log, and its digest added to an MMR. To provide efficient lookups of a key's value, we employ a memory-efficient index that maps a compressed representation of each key to its latest value in the log.

The figure below depicts a small example of this kind of ADB, showing only the updates for key “foo” which is assigned value 5 in log operation 3, deleted at operation 6, and later updated to value 6 at operation 9, which contains its active state. While the contents of the log are durably persisted to disk, the index depicted to the right is memory resident, mapping a key to the location of its currently active operation. Because keys in some applications may be large (e.g. 32 byte hashes), keys are transformed by a user-provided function into a more compact representation (e.g. an 8 byte hash prefix) for memory efficiency. (There is some additional complexity we don't describe here required for handling a small but non-negligible chance of collisions among these transformed keys.)

One challenge with this solution is the endlessly growing log of data which needs to be replayed to derive the current state of the database. Consider the MMR in the diagram above: it stores the old value for key "foo" in operation 3 even though its value is later reassigned in operations 6 and 9. To overcome this, we apply a compaction process that advances the inactivity floor, the index before which all operations are inactive (and therefore don't need to be stored to compute the current state). Starting from the old inactivity floor, we advance over the next n operations, where n is configurable. If the operation is already inactive, we simply drop the data. If it's active, we make it inactive by reapplying the same key-value in a new operation. This process guarantees that the number of inactive operations remaining ahead of the floor is never more than a small constant multiple of the number of active operations. Operations preceding the inactivity floor can be efficiently discarded from disk while still retaining the ability to authenticate any historical operation against the current root. Much as the log supports re-derivation of the database's state, it also allows us to re-derive the state of the pruned MMR as long as we durably persist (aka pin) a small (logarithmically sized) set of historical nodes.

A variety of designs are possible within this general framework for an authenticated database, each involving differing trade-offs between performance, memory efficiency, and authentication expressivity. Our initial release, adb::any, implements the minimal construction described above over the existing mmr::journaled primitive. To limit the IO of both updates and deletes to a minimum, adb::any only supports proving that some key was assigned to a specific value at some point in its history (not that a key has some value now nor that a key has no value). This (lack of capability) achieves a unique balance between performance and functionality that we believe applications will find just useful enough. For example, adb::any can be used to power efficient state sync over the active range (indicated by the inactivity floor), drive message-based interoperability (where emitted messages are forever persisted), and equip users to verify the balance served to them by centralized infrastructure (constraining any future proof to be at an index higher than the last).

Another variant, which remains under development, augments this construction with an authenticated bitmap over the activity status of each operation. This extension allows the ADB to additionally authenticate that a specific value is a key's current value – useful for applications requiring, for example, proving someone's account contains some balance, or that a user currently has the permission to execute some contract. QMDB, the primary inspiration for this work, extends these concepts even further, adding the ability to prove exclusion (that some key is not currently assigned any value).

In addition to assign and delete over keys, our implementation offers one additional database operation, commit, that synchronizes the compaction process with each batch update. In the context of a blockchain, the set of updates from executing all transactions in a block can be atomically committed to the database along with raising the inactivity floor a number of times necessary to prevent it from falling indefinitely behind (a useful marker in the log to inform state syncing clients where to start fetching from the log). This compaction process could be extended to charge any rewritten (still active) account at the inactivity floor some rent or to drop said accounts altogether from “hot” storage (requiring a proof to resurrect when needed again).

adb::any is available today with work ongoing to deliver both additional feature variants and a benchmarking suite to evaluate the impact of said variants. Like other primitives, adb::any is exhaustively tested with runtime::deterministic over a number of failure scenarios (like unclean shutdown).

We look forward to releasing a production-ready version of adb::any later this year.